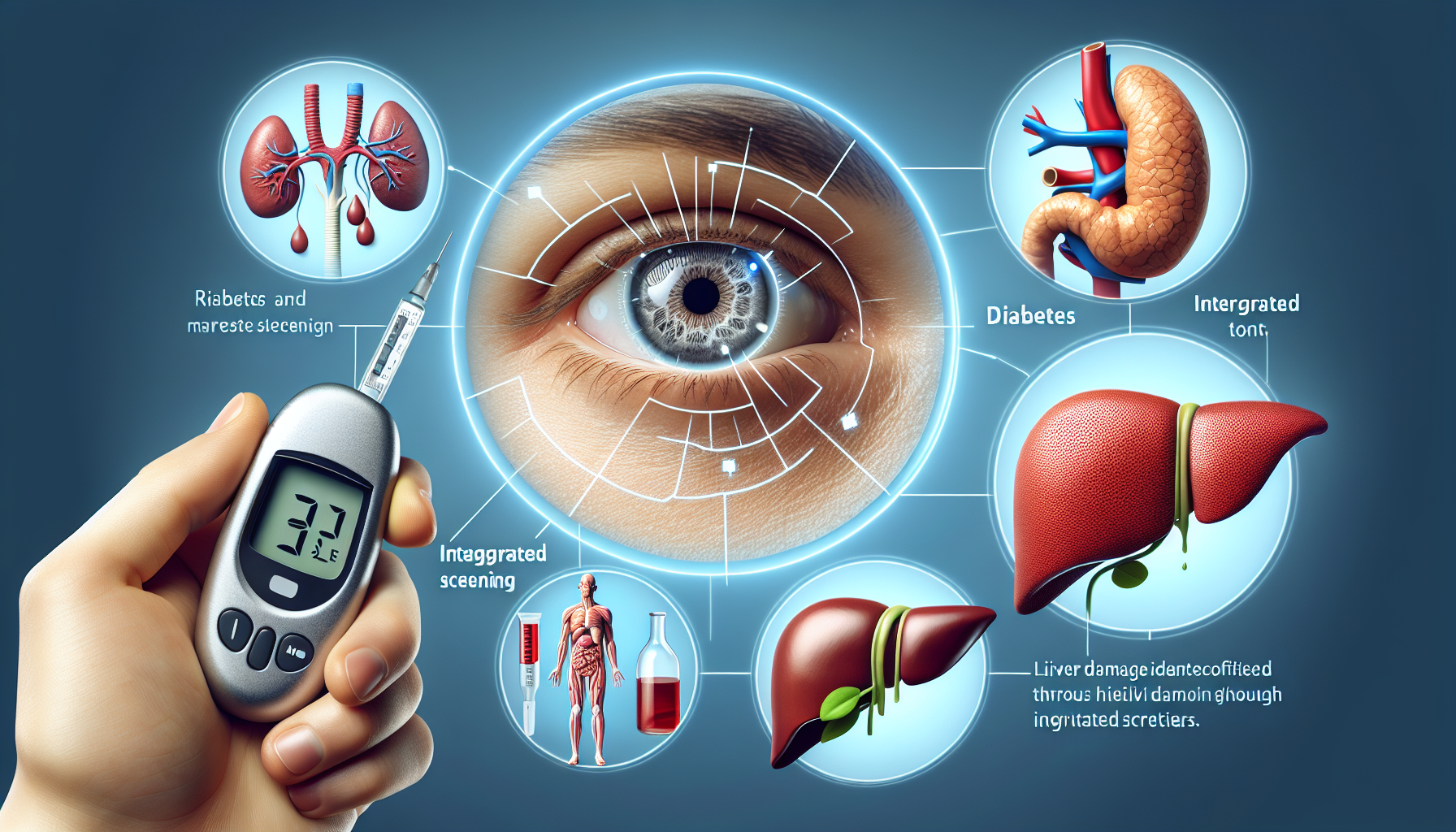

A recent study from the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden has shed light on the potential to screen patients with type 2 diabetes for liver damage simultaneously with eye disease screening. The research, published in Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology, emphasises the importance of early detection for improved patient outcomes.

Liver disease, particularly fatty liver disease, is prevalent in over half the population with type 2 diabetes. However, its early stages often go unnoticed due to the lack of symptoms. If untreated, this disease can progress into liver fibrosis, a condition characterised by liver scarring that could lead to cirrhosis or even liver cancer in the worst cases. Hence, international guidelines advocate liver fibrosis screening in individuals with an elevated risk, including those with type 2 diabetes.

Hannes Hagström, an adjunct professor at the Department of Medicine, Huddinge, Karolinska Institutet, and a consultant in hepatology at the Karolinska University Hospital, expresses concern over the late detection of severe liver disease. He suggests that with the availability of approved treatment for fatty liver disease with fibrosis, regular screening among diabetic patients could thwart the progression into severe conditions.

In Sweden, retina scanning or fundus photography is an established routine for identifying eye damage in people with type 2 diabetes. Hagström and his team of researchers explored the possibility of using elastography, an ultrasonic technique, to concurrently screen for liver fibrosis during retina scanning. Elastography is a non-invasive method that takes minimal time to perform, making it an ideal choice for combined screening.

The study indicates that a significant proportion of patients with type 2 diabetes are open to this combined screening approach. Over 1,300 patients undergoing retina scanning were asked if they would consider a simultaneous liver examination via elastography. An overwhelming 77% of the participants agreed.

Preliminary findings from the elastography examination suggested liver fibrosis in 15.8% of the patients, while 5.0% showed signs of advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. However, upon re-evaluation, these figures dropped to 7.4% and 2.9% respectively, indicating potential false positives. Hagström explains that this could be due to patients not following the fasting instructions prior to the examination.

Hagström concludes that the next phase of the study will involve health economic analysis to ascertain whether this combined screening strategy for eye and liver disease proves beneficial. This study was executed in partnership with the Capio Ögon Stockholm Globen eye clinic, primarily financed by Gilead Sciences and Pfizer, and Region Stockholm.

For more information on eye care and developments in ophthalmology, visit my website, Shankar Netrika Eye Centre. As a leading eye surgeon in Mumbai, I specialise in cataract and laser surgeries, providing comprehensive eye care solutions to my patients.

Comments are closed for this post.