New research from Mass Eye and Ear scientists suggests that a groundbreaking mRNA-based treatment could potentially prevent the onset of blindness and scarring due to proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR), a condition that can occur after retinal detachment repair or a severe eye injury. At present, surgery, which carries its own risks of PVR, is the only available treatment. This exciting development, published in Science Translational Medicine, offers a glimpse of what future mRNA therapies could offer PVR patients, as well as those suffering from other retinal diseases.

The researchers have heralded the treatment as the first successful application of mRNA-based remedies within the eye. Dr. Leo A. Kim, MD, PhD, the Monte J. Wallace Ophthalmology Chair in Retina at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, and co-corresponding author of the study, expressed his delight at the unexpected success of this approach in the eye, with minimal inflammation. The team hopes these initial findings will pave the way for new treatment options for PVR and a range of other eye diseases.

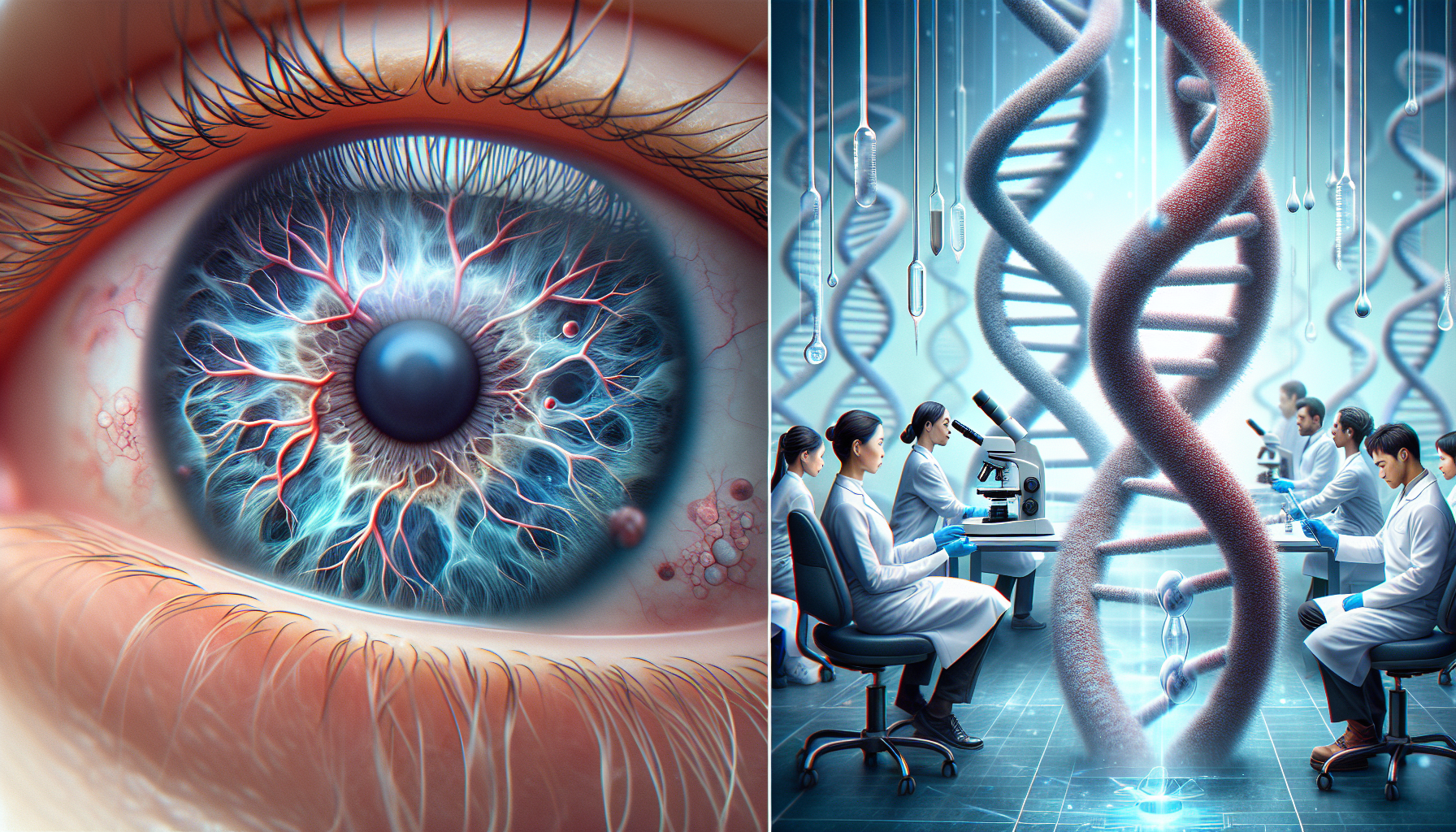

PVR, a condition involving the growth of scar tissue within the eye, often occurs after traumatic injury. The scar tissue can contract and detach the retina, leading to blindness, a reaction more detrimental than the initial injury itself.

The groundbreaking research explores the use of mRNA as a therapeutic in the eye. In simple terms, mRNA is a cellular messenger that carries genetic code to ribosomes in the cell, directing them to create proteins. This process is crucial for the cell’s structure and functionality, including regulating gene activity.

The research team utilized cell-based, tissue-based, and preclinical models of PVR, demonstrating the safe use of mRNA-based therapeutics in the eye. The team focused on various mRNAs linked to scar tissue formation, targeting a protein called RUNX1. This protein controls the gene expression that transforms eye cells into scar tissue.

The researchers initially planned to target RUNX1, but technological limitations posed a challenge as mRNA is typically used to increase protein expression, whereas in PVR, there is an overproduction of RUNX1. The scientists then developed an innovative therapy, based on the creation of a molecule to trap RUNX1 and inhibit its function – a technique known in biology as a dominant-negative inhibitor.

The team developed an mRNA called RUNX1-Trap, which restricts RUNX1 in a cell’s cytoplasm, preventing it from reaching the nucleus and activating the gene responsible for transforming cells into scar tissue. Their findings revealed a successful halt in scar tissue and abnormal blood vessel development in patient-derived cells in lab culture, animal models, and patient tissues in the lab.

While this research is still in its early stages, the team views it as a promising proof of concept for PVR and other eye diseases. However, the methodology has not yet been tested on human subjects, and there are limitations to the technology, as mRNA doesn’t stay in the cell for a prolonged period of time. This raises questions about the duration of effects from a single treatment and whether multiple doses over an extended period may be necessary for effective PVR prevention.

The researchers are now investigating methods to extend the half-life of the mRNA for longer-lasting effects and to determine the optimal treatment timing. They also hope to extend the use of their mRNA system and RUNX1-Trap therapy to treat other retinal conditions, such as wet age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy.

In conclusion, the researchers are optimistic that targeting RUNX1 could lead to new therapies for sight-threatening conditions and potentially effective treatments for other diseases, expanding the potential uses for mRNA. The groundbreaking work is the result of a substantial collaborative effort from a multidisciplinary team and opens new avenues for the application of mRNA technology in ophthalmology and beyond.

Comments are closed for this post.